AI Model Thresholds: How Governments Can Identify Frontier AI Systems

Strict regulations for every AI system would likely hinder innovation and overwhelm regulators. But doing nothing about catastrophic risks from frontier systems would be a mistake.

One solution is setting model thresholds: well-defined boundaries to define which AI systems are covered by regulations.1This is true for most model governance regimes: where your regulation is focused around AI models. Alternatives include company governance, where you might have company thresholds instead (e.g. a company which spends £1bn+/year training AI models’).

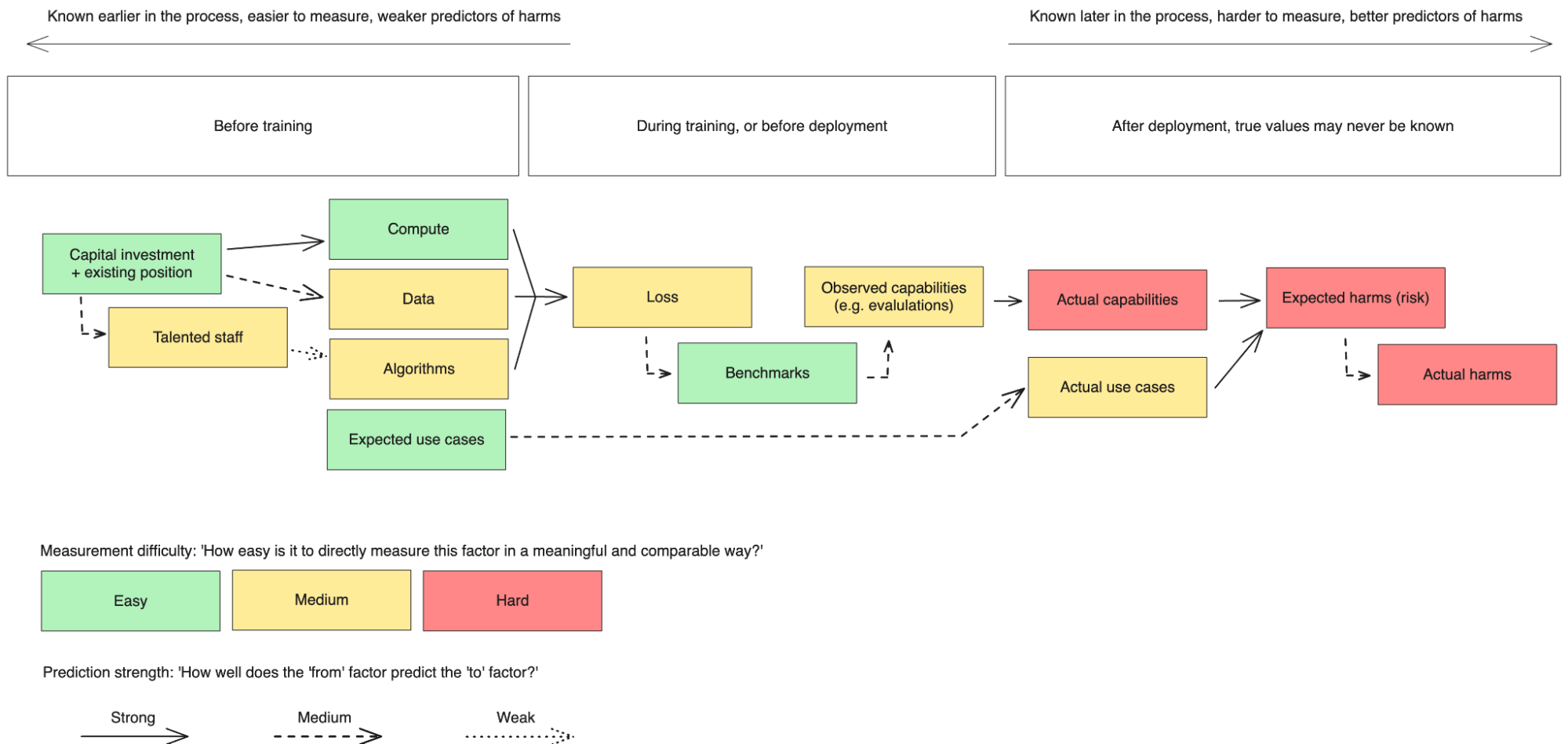

This report examines different options for these thresholds: from compute, benchmarks, data, and more.

Key findings:

- Compute (the amount of calculations used in training) is one of the best options for setting thresholds e.g. ‘models trained using more than 10^26 FLOP’

- Compute alone misses high-risk narrow models that might be used for bioengineering or weapons systems. Benchmark thresholds e.g. ‘models that score over 80% on a specific multiple-choice test like WMDP’ may be helpful here, although it’s hard to predict which benchmarks are relevant in advance.

- Threshold values would likely need to be updated over time, sometimes at short notice, to account for new developments (e.g. algorithmic breakthroughs, AI risk resilience).

What is a model threshold? Why might we want them?

A threshold is a well-defined boundary that aims to classify a model. For example, a threshold might be ‘a model costing more than £100M to train’.

We might use thresholds to enable proportionate regulation. For example ‘if you pass threshold X, you need to register with a regulator’ or ‘if you pass threshold Y, you have to conduct dangerous capabilities evals’.

What thresholds might we use?

There are several types of thresholds, some based on ‘AI scaling laws’ (closely linked to the ‘AI triad’). These scaling laws are empirical statistical laws that suggest the three key predictors of AI model performance are compute, data and algorithms. Therefore more compute, more higher-quality data, and better algorithms would indicate a more powerful (and thus potentially more risky and relevant to regulate) AI model. Scaling laws describe continuous trends, they do not enable prediction of precise capabilities (e.g. arithmetic, rhyme writing) which could happen by surprise and discontinuously.

The most promising threshold types are compute, benchmarks and data - and especially compute. These are harder to game, easier to define clearly, and track AI progress fairly well. Compute and benchmarks are also easier to spot non-compliance in, by monitoring supply chains or external evaluation of publicly accessible models. Additionally, compute and data offer thresholds before training takes place: allowing for earlier identification and therefore easier mitigation of risks, and allowing businesses to better forecast regulatory requirements.

Note: numbers used are notional and not based on any expert judgement - they are just placeholders to make the examples more concrete. Do not anchor actual thresholds on these numbers!

Compute

Compute: The amount of computer processing that has gone into a certain activity. This is the product of ‘how fast can your computers process things’ and ‘how long do you let them do this processing’.

Measurement

- We can measure this product in floating point operations, abbreviated as FLOP (confusingly, FLOPS is used to mean ‘floating point operations per second’ - not the plural of FLOP). There are sometimes difficulties in doing this because some algorithms might be using other types of operations that might not be directly comparable. However, in almost all cases some reasonable approximation can be made, and it’s been a measurement used since the 1960s so appears robust to technical progress.

- Sidebar: What is a FLOP? A floating point number (or ‘float’) means a number with a decimal point, like 3.14 or 0.6 or 243.0. An operation is something like addition or multiplication. A FLOP is a single FLoating point OPeration, i.e. adding or multiplying some numbers with a decimal point. Training an AI model requires huge numbers of FLOP.

Advantages

- It’s a good predictor for model performance

- It’s clear how to measure

- It’s objective and harder to game.

Limitations

See full article on problems with compute thresholds

Example threshold: ‘training a model using more than 10^26 FLOP’

Benchmarks

Benchmarks: Performance on standardised tests, like giving the AI an exam.

Measurement

- Concretely, this looks like having a model complete a set of exam questions, marking their results, and giving them a score. For example, the MMLU benchmark is one such ‘exam’ that contains multiple choice questions for language models that covers mathematics, psychology, biology, politics, law and medicine. Being multiple choice allows for easy automated grading to be done inexpensively and at scale.

- Benchmark performance could be measured at snapshots during training and at the end of training. Additionally, it could be predicted before training by experts at the AI company following a template process based on the scaling laws - however this is difficult to do accurately, as some capabilities are “emergent” (appear unpredictably in the course of training).

Advantages

- Benchmark thresholds might be more robust to change than compute, given that they represent some level of capability which we consider ‘potentially dangerous’: which probably will move relatively slowly over time as the world becomes more resilient to AI risks.

- Specific benchmarks might inform certain risks - for example scoring well on a bioweapons knowledge test (like WMDP) might suggest the model does have the capability to help bioterrorists.

Limitations

- Benchmarks are somewhat model dependent: asking an image generation model to generate text, or a text model to generate images would probably give us a very wrong picture of a model’s capability and therefore risk.

- Much like how performance on a multiple-choice law exam is an imperfect predictor of a person’s abilities as a lawyer, AI benchmarks can fail to capture a model’s abilities at real-world tasks requiring interaction with the world or “common sense”. But this limitation may be true of any easy-to-evaluate threshold; compute also predicts real-world impact imperfectly.

- Benchmarks can be gamed by bad faith actors. For example, if MMLU was chosen as the benchmark, a company wishing to skirt regulatory scrutiny could design their model to be awful at multiple choice. We could mitigate this somewhat by requiring developers to fine-tune their models on MMLU-like questions, or getting them to explain what benchmarks they use internally when deciding whether a research route is promising.

Example threshold: ‘training a model that is expected to get more than ≥85% questions from the MMLU correct’

Data

Data: The data used to train the model. This is slightly harder to define in a measurable way than compute, because there is some combination of data quantity, data quality and data leverage.

Measurement

- Quantity can be measured in bits, the number of zeros and ones required to store the information (or bytes, as 1 byte = 8 bits) - this is how file sizes on your computer are measured. However, this varies substantially for different types of models as text is generally much smaller than images or videos: the complete works of Shakespeare is ~6MB, yet a single film on Blu-Ray is ~50,000MB.

- Quality may be context dependent: e.g. raw personal email data might be great for a model to classify spam emails, but less useful (although still useful) for a model that’s designed to write helpful and respectful customer service responses. This tends also to be a much more qualitative measure (although there are techniques for identifying ‘information value’, these are somewhat underdeveloped). Additionally, data quality may inform the risk of certain types of training: for example if AIs are trained on biassed or erroneous data they might exacerbate bias or errors - and this could be amplified if models were repeatedly trained on the outputs of previous AIs.

- Leverage is how much certain data affects the final model. For example, pre-training (building the base model) typically uses an enormous amount of data whereas fine-tuning (tailoring the model to focus on specific capabilities) is comparatively much more sample efficient; so an extra unit of fine-tuning data probably matters a lot more than an extra unit of pre-training data.

Example threshold: ‘training a model using more than 10^15 bytes of text data’

Loss

(Log) Loss: A technical measure of how far away from perfect the model is in its predictions, often used by AI developers to see how their model is performing over time (lower loss is better).

Measurement

- When models become better predictors, they usually perform better in terms of their general capabilities, and therefore potential to cause certain types of risk (the flip side of this is that models with high loss are often less accurate which may lead to other risks, especially to do with bias or making mistakes).

- Sidebar: What is log loss in language modelling?: Loss is specifically how different the predicted output is from the correct output during training. For example, if we are training a language model using the data ‘the cat meows’, we might give the model ‘the cat’ and ask it to predict its best ideas for the next word. We see how confident the model was that the next word should be ‘meows’: if for example it thought there was a 1% chance of the next word being ‘meows’ it would score badly (high loss), but if it thought there was a 99% chance of the next word being ‘meows’ it would score well (low loss). Log loss refers to a number derived from the loss using the logarithm function, which amplifies bigger mistakes of confidence (e.g. if the model was 99.99% confident the next word is ‘chair’, this is penalised much more than if it’s only 10% confident).

Limitations

- Because loss tends to be how well the model makes predictions about data, loss varies a lot with different datasets. Additionally, log loss can sometimes be computed in different ways so if used, some technical standards are necessary - although even with these it may still be difficult to set a reasonable threshold value.

- Log loss can be misleading for predicting capabilities advancements, especially for models trained with reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). This is because the log loss metric might be effectively computing ‘how far away is this text from the average twitter post’: so models trained with RLHF to write complex, well-reasoned long-form content are likely to be far from this. Given that benchmarks can generally be performed fairly early on also very cheaply, they might be a generally better alternative.

Example threshold: ‘a language model which attains an average log loss metric <0.001 on a known set of social media data’

Capital investment

(likely to be less useful) Capital investment: How much money is being spent by a company on frontier model development over a time period, or maybe on a single model.

A similar alternative approach might be looking at R&D investment as a percentage of total AI R&D, or just foundation AI model market share percentage.

Advantages

- Investment as a metric does probably roughly scale with risk, and may be more resilient to having to be changed than compute thresholds.

Limitations

- This might be easier to game (as people can argue whether something is or isn’t AI R&D), and might also just be quite difficult to define sensibly to capture R&D that pushes the frontier versus that just adds business value without creating significant new risk.

Example threshold: ‘models expect to cost more than £100 million’

Talented staff

(likely to be less useful) Talented staff: Number of relevant technical staff.

While it’s very hard to predict exactly where algorithmic improvements might appear, having many talented technical staff is likely to support these breakthroughs. Therefore it might be desirable to monitor organisations with a high concentration of technical talent.

Measurement

- This could simply count the number of relevant technical staff. Although defining ‘relevance’ may be tricky.

- Alternatively, the threshold could be set as a percentage of the organisation, to understand how focused the organisation is on frontier model development. This is to avoid encompassing very large organisations with a few AI experts sparsely scattered across them: although this logic might not hold up if these staff were concentrated on a few teams.

- Another alternative is to consider spending on technical staff (again either in absolute terms, or as a percentage of total salaries). This might help capture where there are more senior technical people or where AI seems to be a major focus for the organisation.

Limitations

- Setting thresholds based on talented staff also suffers from the same problems as R&D investment in defining who exactly meets the criteria for being a relevant technical staff member.

- Technical talent density can sometimes be more important than the sheer number of people - it is possible this might mean small but highly capable startup-like teams are overlooked.

Example threshold: ‘models developed by companies with more than 50 FTE researchers working on developing new AI techniques’

Opt-in

Opt-in: Allowing companies to self-identified as producing frontier or high-risk AI system, where they feel they would benefit from regulatory oversight.

This would help capture a ‘miscellaneous’ category, and enable people who are keen on safety to collaborate with regulators. This feels particularly useful where a company might not be included by the other metrics, but could still be doing something dangerous.

Some reasons companies might opt-in by choice might include:

- being able to advertise that they are regulated/compliant in some way - although we should be careful to avoid the framing that being regulated has eliminated all risk

- if they believe they might exceed a mandatory threshold for regulation soon, it might be more efficient to start preparing with a more softly enforced opt-in ruleset

- being able to shape future regulation e.g. by opening a communication channel with government, or participation in sandboxes

- they may genuinely care about safety: companies are made up after humans after all that care about things going well in the world.

It is also plausible that some people might self-refer themselves, but they are not the kind of organisation a regulator cares about monitoring closely. In these cases, there should probably be a mechanism of ‘rejecting’ applications to avoid creating unnecessary burden on a regulator.

Example threshold: ‘companies that have self-referred a model to a regulator as a frontier AI system’

Use cases

Use cases: Some AI risks will be mostly dependent on their actual use in the real world. Models targeting a specific use case might be higher risk than others, especially AI models relating to bioengineering, weapons control systems and offensive cybersecurity capability. Further sectors are likely to be identified over time.

For example, a narrow AI to support biologists working on synthetic biology might increase bioterrorism related risks but could plausibly use significantly less compute or data than more general models.

Example threshold: ‘models that are reasonably expected to be used in weapons control systems’

Compound thresholds

Compound thresholds: Some combination of all the above.

It may be that a single threshold might not be the way to go. It’s likely that some combinations of the above matter more or have dependencies that we can express by joining them up.

In the simple case, this might be joining up thresholds with ANDs and ORs. In the more advanced case, it might be some mathematical function of factors: e.g. sum several different factors, or apply some multipliers.

Example threshold: ‘(models trained with over 2.5 threshold units, where there is 1 threshold unit for each 10^26 FLOP + 1 threshold unit for each 10^15 bytes of text data + 1 threshold unit for each 10^19 bytes of image data) OR (models trained to engineer new biological viruses)’

Footnotes

-

This is true for most model governance regimes: where your regulation is focused around AI models. Alternatives include company governance, where you might have company thresholds instead (e.g. a company which spends £1bn+/year training AI models’). ↩